Read David Gilmour Summer 2008 Interview for Mojo. Great Read!

Mark Blake has kindly given NPF permission to re-produce his interview he did with David Gilmour in the summer of 2008 before the death of Richard Wright. The interview was for MOJO magazine. Highlights in the interview include news of the 5.1 Wish You Were Here mix, possible future David GIlmour solo albums and the final word on Pink Floyd touring again!

Free prize draw to win 15 signed copies of Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story Of Pink Floyd.

Subscribe to Mark Blake’s newsletter and your name will be entered into a prize draw to win a signed copy of the paperback edition of Mark’s book Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story Of Pink Floyd. The winners will be announced after the draw on February 1st 2009. Current subscribers will automatically be entered. Subscribe here.

DAVID GILMOUR UNABRIDGED INTERVIEW

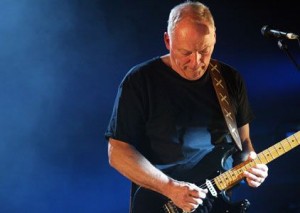

The Norwegian Lavvu is not to be confused with a tipi or yurt, as David Gilmour is keen to explain. The Lavvu was a present from his wife and co-writer Polly Samson and the large, conical tent, ideal for sleepovers and cookouts, stands in the vast grounds of the 62-year-old guitarist’s Sussex farmhouse. Alongside it is a converted barn studio, in which Gilmour created most of his last solo album, 2006’s Number 1 hit, On an Island, and in which he is now sat, barefoot, and supping from a mug of strong builder’s tea.

A rack of guitars fills one corner of the room. Under the window, stands a battered pedal steel, covered with rehearsal notes from a recent performance of Atom Heart Mother; the Pink Floyd album more famous perhaps for the cow on its cover than the music inside.

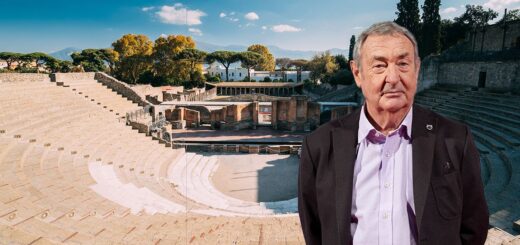

Gilmour is here to talk up the release of Live In Gdansk, an album of a concert to celebrate the 26th anniversary of the founding of the Polish Solidarity trade union movement. In the album’s accompanying DVD, the Gilmours dine with former Solidarity leader and ex President Lech Walesa, who reveals through his translator, that, like Gilmour, he has eight children but that “all I can do now as far as male things go is shave”.

In recent years, for David Gilmour, being a father and husband seem to have taken precedence over music. The On An Island tour was a relaxed, family affair (“and people wonder why I don’t want to go back to Pink Floyd”). The man himself once compared his old band to “a great, lumbering behemoth”, but things also move at glacial slowness in David Gilmour’s world. There were six years between his first two solo albums, and 22 between the second and third. A fourth one may take a while yet. Being a Gilmour watcher is akin to being a ‘twitcher’ huddled in a dug-out – or Norwegian Lavvu, perhaps – waiting for a rare species to show itself. Today, though, the lesser-spotted Gilmour is on witty good form and absolutely raring to go…

MB: How did you end up playing in Gdansk?

DG: We were invited to play Poland, and it sounded like a great idea, to be celebrating that first move towards Democracy. Being the last night of the tour as well, it was emotional. It felt rather strange to be in this shipyard which is now practically derelict, and which is about to be sold to a property developer.

MB: What did you make of Lech Walesa?

DG: Very upfront and blunt, the qualities that got him where he is today. It was an enjoyable meeting, but they gave us this very strong drink – like Schnapps – and immediately afterwards I had to go into a press conference. So after being forced to knock back two or three of these things, I was being asked a question about Roger Waters.

MB: In August 1980 when Walesa led the striking shipyard workers, Pink Floyd had just played The Wall at Earls Court. How much did events in Poland impinge on you all at the time?

DG: Very much so. I remember it well. It was fascinating moment in history, which started all that rumbling of discontent that led to the Berlin Wall coming down. One doesn’t want to be anti-socialist, but I think of that whole Eastern European movement as being against oppression and promoting personal freedom more than anything else.

MB: Both your parents were teachers in Cambridge, how politically active were they?

DG: It was just all around us at the time. My parents were on the left of centre; proper Manchester Guardian readers. Some of their friends went on the Aldermaston marches. Mine never did to my knowledge, but they were both committed to voting for the Labour Party. I still consider myself to be more a socialist than anything else, even if I can’t quite stick with party politics.

MB: For years, you shared Pink Floyd with a musician who seemed to have a much louder political voice…

DG: Roger [Waters] has a loud political voice but I don’t know how much he actually uses it. He would say that he uses it within his music.

MB: Waters’ opposition to The Falklands War was the theme behind much of Pink Floyd’s The Final Cut in 1983. How comfortable were you sharing those views?

DG: Roger and I had disagreements, but we were from the same side. I am completely against war if it can possibly be avoided, and I was not in favour of Thatcher going in to the Falklands, but my view was that it was our job to support that territory, and that in one way or another there should have been some longer term agreement mapped out. It seemed obvious that there was a rather deliberate breakdown of communications between the diplomatic channels of the Argentine and the UK, in order to create a scrap… That mass murder on the General Belgrano was just appalling.

MB: Could you ever see yourself combining music and politics?

DG: I have nothing against any musician wanting to use their voice as a musician expounding their philosophical or political views. Bob Dylan’s early very hardcore political songs are what I grew up with. But I admit I’m not really vocal enough and clear enough. I’m afraid, I live my life lives in shades of grey.

MB: Any regrets now about playing Live 8?

DG: Not at all. But there are still stories popping up about things that were agreed in conference that still haven’t been lived up to by various countries. One can only hope.

MB: You donated the £3.6 million proceeds of a sale of a house to Crisis. Most people will wonder what it feels like to give away that much money?

DG: Let’s not get blasé about this, but [pauses] I am quite a rich person. And I have written cheques for some pretty big sums of money, though that was probably the biggest. It was a house that was being sold and I was going to and put the money into a charitable trust that Polly and I administer, but Polly, who is much better at these sort of things said ‘No. Bang! Just do it all and it will generate loads of publicity for the charity’. And she was right.

MB: Do you remember your first paying gig?

DG: I doubt if I played for money before the age of 17. The first band I was in was called The Newcomers and we were pretty crap. But before that, I did an audition and a day with another band whose name I can’t remember and played a gig at a village college in Cambridgeshire. It was only when I met we started a covers band, Jokers Wild [in 1964], with this idea of doing big, harmony vocals, that I felt I was doing anything worthwhile.

MB: Were you offered a solo deal around this time?

DG: Someone might have said something along the lines of, ‘We could offer you something but you’d have to lose your band’, but I was too scared. I wanted the band around me.

MB: You met Brian Epstein around this time.

DG: Yes. He never offered me anything specific. We also saw Jonathan King, Lionel Bart…[smiling]

MB: You were a fresh-faced lad…

DG: Yes… That was the thing. All these people were gay it has to be said, and I wasn’t. Epstein seemed very nice, but I don’t think my perceptions of what was going on were entirely accurate in terms of what was really going on.

MB: Andrew Loog Oldham and his business partner Tony Calder also said they came across you around this time.

DG: We auditioned for Andrew Loog Oldham. But I also did something with two other musicians that I worked on at those auditions, Wally Waller and John Povey, who went on to join The Pretty Things. The trouble is, I was comfortable in my having the protection of a band around me, and I wouldn’t have known where to start on my own.

MB: When did you first start trying to write songs?

DG: With Jokers Wild it was all about getting people dancing, not sitting down listening. But later on, that became restrictive, so I tried to write when the band [a later version of Jokers Wild, known as Bullitt and Flowers] were living in France [1966 and 1967]. I have a memory of one song, actually, which I am not going to divulge. I’m that ashamed [smiling].

MB: I’m trying to imagine what David Gilmour, the songwriter, would have sounded like then.

DG: I don’t think I could have ever seen myself as a solo act. Maybe it was laziness, but that pithy acerbic political stance taken by Dylan was never going to be my forte. I was a major Dylan fan, but I didn’t think I could do that myself. Again, I liked the idea of having that little support network… even if we might later rather laughingly call Pink Floyd a support network.

MB: Around this time you saw Hendrix. How much of an influence was he?

DG: A major influence, in terms of playing, but it’s hard to tell how the people you admire affect you when you start writing. It’s that thing about how music sounds in your head compared to how it comes out. The music I heard in my head came first from Leadbelly and then The Beatles and Eric [Clapton] and Hendrix. What it distilled itself into is another matter.

MB: When the covers band came back from France, the rest of them returned to Cambridge, but you stayed in London, determined to start another band. Is this the first indication of that stubborn streak?

DG: I’d been living in London before we went to France and my parents were in America. So I didn’t have a family home in Cambridge to go back to. My parents had gone off for six months when I was five and put me in a boarding school. Then they’d gone off again for a year when I was 15. My parents definitely instilled independence in us.

MB: So they didn’t object to you wanting to be in a band?

DG: No, which is unusual for parents at that time, but they didn’t have much choice. I hadn’t completed my A-Levels, so going to university or into any sort of normal career was long past. My parents actually loved the whole idea of me being in a band. They couldn’t get enough of coming to gigs, even, later, when I was in the Floyd. They’d come and help lug a bit of gear. When they were living in New York and I was 15 they sent me the whole of the 1959 Newport Folk Festival – all three albums and then Bob Dylan’s 1st album, which I got on my 16th birthday in March ’62. It had been recorded in December ’61 and wasn’t out in England.

MB: Back in London what was the plan?

DG: Form another band and do original material. But I had no firm idea of whom I should be forming a band with. I’d only been back in London for two or three months, when the offer came from Pink Floyd. Did it feel weird to join them? They were the local boys made good and we’d done two or three gigs together when I was in Jokers Wild.

MB: There’s a video of Pink Floyd miming to See Emily Play in 1968. Rick Wright is pretending to sing Syd Barrett’s vocals, Nick Mason is miming without a drum kit, Roger Waters is using his bass as a cricket bat and you’re looking pretty embarrassed by the whole things. What was going through your mind?

DG: I was still trying to get used to it. It was very odd those first couple of years, stepping into Syd’s shoes, working out what we were going to do. I remember it being different in the studio, though, where I was loud and bolshie, letting them know that I was there and taking part.

MB: When did you start writing on your own?

DG: I don’t think there was anything before Fat Old Sun [on 1970’s Atom Heart Mother] was there?…

MB: You get a sole writing credit for The Narrow Way on Ummagumma [in 1969]. Was that the very first piece you wrote lyrics for with Pink Floyd?

DG: It must be, but I have never listened to it since. I experienced abject terror when it was suggested we all write a song each: ‘Right, then, you’ve got a 10-minute slot to yourself’. ‘What?’ We were at a loose end with Ummagumma. We didn’t know what the fuck else to do. In the meantime, Roger was developing himself as a lyricist, and my own paranoia – and laziness – combined with his ascendance created this situation where I largely did music and he did lyrics.

MB: Were you ever jealous of Roger’s abilities?

DG: There’s no one else’s talent I would have swapped with my own. There are moments when one is jealous but it’s usually an irrational thing. If you go back through those albums, Atom Heart Mother and then Meddle, you can hear me growing in confidence and assertiveness.

MB: You experienced huge success with The Dark Side Of The Moon and Wish You Were Here, and then there’s [1977’s] Animals, by which time it’s claimed that Roger was dominating the rest of the band. You only had one co-writing credit on Dogs.

DG: Roger’s thing is to dominate, but I am happy to stand up for myself and argue vociferously as to the merits of different pieces of music, which is what I did on Animals. I didn’t feel remotely squeezed out of that album. Ninety per cent of the song Dogs was mine. That song was almost the whole of one side, so that’s half of Animals.

MB: Six months after the Animals tour, you went off and made the ‘David Gilmour’ solo album.

DG: I was persuaded to do it by Rick [Wills, bass] and Willie [Wilson, drums], the guys I’d played with in France before I joined Floyd. It was three weeks. Job done. I last listened to it before we started the On An Island tour. There’s No Way Out Of Here is lovely song but I am excruciatingly embarrassed by some of others. No, I won’t say which ones. I never saw that album as the beginning of anything.

MB: Did you ever consider then that there might not be another Pink Floyd album?

DG: No, never. You guys want a story, but it’s like an episode of EastEnders where you’re concentrating all the bad moments into a small thing, and that squeezes out all the good moments. There is no reason why you shouldn’t do that because you want a good story, but there is an imbalance in the perception of disgruntlement between us at this time. That first solo album came out of my frustration at how drawn out things were becoming in Pink Floyd… before heading back into another Floyd album that took even longer [laughing] …The Wall.

MB: By which point there was disgruntlement?

DG: Yes, but the rows were all about music. I can also remember me and Roger sitting in the studio, going, ‘Wow, this is fantastic, what we’ve just done’. But Roger’s dominance did become an issue. I don’t think he consciously wanted to do people down, he was just being himself. Sometimes it’s hard to be sensitive to how much your characteristics can hurts other people. Also, everybody who got damaged by these things was as much to blame for it at the time as anyone else.

MB: By now, you’d produced a band called Unicorn and been introduced to Kate Bush. Were you ever tempted to go off and produce more people?

DG: No, outside production is a thankless task. I produced Kate’s demos because I thought she was a real talent. The only A&R record company people I knew at EMI were cloth-eared gits. I thought, I can’t play them Kate warbling away and playing a piano. They won’t get it. So I made a demo of releasable standard to get her a deal. I did wind up producing Unicorn, but they were so self-effacing, they were never going to make it big. Raw talent is never going to be enough. Massive drive is needed. There are hundreds of examples where it was massive drive – Marc Bolan, though perhaps I shouldn’t say that. And, yes, at the other end of the spectrum you’ve got Roy Harper. Very talented, but he’s his own worst enemy most of the time, old Roy.

MB: Your second solo album, About Face, arrived in 1984, by which time Pink Floyd was in disarray.

DG: I was frustrated that the whole Floyd thing was falling down, and just wanted to go and have another bash on my own, but get some of the top guys in the world [including Stevie Winwood], to have a bash with. I had this fantastic little team of players and went of to Paris and knocked out some tracks.

MB: You co-wrote two songs with Pete Townshend.

DG: We’d done some recording for The Final Cut at [Townshend’s] Eel Pie Studios, and Pete had told me had really liked my first album. I was dumbstruck, but he said he was having difficulty writing music, but had loads of words. I sent over two or three tracks and he came back with lyrics for Love On The Air, All Lovers Are Deranged, and a third one, White City Fighting, which ended up on his next album.

MB: Were you now seriously considering a solo career by now?

DG: I suppose I must have been. I toured About Face on a thin-wallet level and it made a profit. The fact is I was facing the possibility that a solo career might now become a necessity. At that time Roger had not actually left Pink Floyd, but we were all at each other’s throats. It was actually in December ’85 that Roger sent off his letter to EMI and he was out of the whole thing. It meant we could carry on. There was never a point after that where I thought that we wouldn’t carry on as Pink Floyd.

MB: This seems to be another point at which your stubborn streak came back to the fore.

DG: Yes, I am pig-headed and stubborn, but often your best characteristics can also be your worst. There have been times when those characteristics has been enormously helpful to me and other times when it has been destructive too.

MB: In what way?

DG: You could say that my refusal to kow-tow to what was going down with Roger was destructive to Pink Floyd staying together, but at the same time what it would have become if I had kow-towed anyway?

MB: What would the next Pink Floyd album have sounded like if you’d made it with Roger Waters?

DG: God knows? By The Final Cut, I’d grown too weary of fighting to assert my musical judgement.

MB: By 1986 you’re in charge of Pink Floyd, bringing in Nick Mason and Rick Wright [the latter had quit in 1981]. The comeback album, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, also lists numerous session players and five co-writers.

DG: Yes but of those session players some just played small bits on songs. With that album I was feeling free to do pretty much as I felt like. We entered the studio without a game plan – that’s true. But that’s often been the case with Pink Floyd.

MB: Did you miss Roger Waters as a co-writer or even a presence in the studio at this time?

DG: If I did, I wouldn’t remember it. I just got on with it.

MB: A September 1988 article in Penthouse, featured Roger Waters claiming that after hearing some of the new Floyd material in progress, CBS Records executive Stephen Ralbovsky suggested you should start again…

DG: A tissue of lies [emphatically]. I never stopped and started again. If you think any record company person was ever going to tell us what to do. We have had a long history of saying, ‘Fuck off, we will deliver our record when we are ready to, with the cover, and you can sell it’. Steve Ralbovsky did come down and wanted to hear a few things. He was a mate. It is entirely possible he wasn’t impressed with it. We’d only been at it for three weeks, and there was a track that I had played him a year before that I’d done at home with [the drummer] Simon Phillips. It was a ripping track, very exciting, but it wasn’t going to fit with anything here. Steve said, ‘What happened to that one?’ I said it wasn’t going to make it. And whatever his thoughts were, he kept them to himself, and wasn’t invited to do anything else. We carried on and by Christmas we had upped a gear and we were on our way forward.

MB: What do you think of A Momentary Lapse Of Reason now?

DG: There are some lovely moments on it – Sorrow, On The Turning Away, Learning To Fly. But, like most people, we got trapped in this ’80s thing. We were a bit too thrilled with all the technology that was being thrown at us, and Rick and Nick were both pretty ineffective.

MB: Under-rehearsed?

DG: I don’t think that’s what it was. [Long pause] No one feels comfortable going there and discussing it: Nick doesn’t, Rick doesn’t and Roger doesn’t. The thing is, within a month of us starting the Lapse tour, Nick and Rick were back, but, of course, I’d got these other guys on board as well [extra percussionist Gary Wallis and second keyboard player Jon Carin]. Yes, Jon is brilliant, but Jon is not Rick, although he can do a bloody great facsimile.

MB: Gilmour re-convened Pink Floyd for 1994’s The Division Bell. He found his co-writer in the journalist and author Polly Samson, whom he married in July that year.

DG: I cannot talk about anything past The Division Bell without crediting Polly with her help in firing me up. She has been so good for me, this person. But, we still have to deal with criticism. The Great Yoko Ono factor, I guess… I think we made some of the Pink Floyd classics in our later incarnation. High Hopes from The Division Bell, which I wrote with Polly, certainly falls into that category.

MB: How different has it been touring with Pink Floyd and with the On An Island band?

DG: Pink Floyd are legendary for non-communication, but at the same time if you didn’t like someone you just said it. The whole thing with hired guns is that they learn to bite their tongues and do what they’re told. You are very clearly the boss. But as time went on with this tour, they started really growing into it and learning how the music should be and take more risks with what we’re doing. It was immensely satisfying.

MB: Rick Wright has said that the On An Island jaunt was the easiest tour he had ever been on. Praise, surely?

DG: During that early-’80s moment it was easy to forget Rick’s abilities because he forgot them himself. But to see and hear him on my last tour, he has come right back out of his shell. Of course, Rick has always been a bit grumpy about things. He still says things like, ‘Well, that’s not quite the musical direction, I thought we should be going in.’ He’s said that about every record we’ve ever made. That’s just Rick.

MB: In May 2006, Wright and Nick Mason joined Gilmour to perform as Pink Floyd, alongside other guests at a Syd Barrett tribute concert at London’s Barbican. Roger Waters also performed, but not with Floyd. What happened?

DG: Initially I wasn’t going to play the show. In fact, I was in a doctor’s waiting room here in Sussex at 3pm that day, and I was grumbling about it, and Polly said, ‘Look, just call them up and stop fucking moaning ‘. So I did. We rehearsed Arnold Layne in the dressing room, and we did say to Roger, ‘Can you do it?’, and he said, ‘I can’t. I have to go and pick someone up from the airport. I’m sorry.’ We knew people would make a lot of fuss and read something into that. Which they did. We were rusty and unrehearsed, but once we got up there, it was fine. I thought one or two of the other performers were great. I really liked Damon Albarn doing Syd’s Word Song.

MB: In June, you played Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother suite with its co-writer Ron Geesin at London’s Cadogan Hall…

DG: Ron persuaded me to do it. I did enjoy it on the night but… I think it’s a pretty flawed, weak track, and I don’t diverge from that view. But sometimes you have to try these things in life. It’s a challenge.

MB: Have you been asked to participate in The City Wakes, a week-long art and performance tribute to Syd Barrett in Cambridge in October?

DG: Yes. But I did my tributes to Syd on our last tour [where Gilmour played Dominoes] and I suspect that’s where I’d rather leave it. I loved the guy, he did some great songs, but I can’t do anything for him now.

MB: Is the 5.1 Surround Sound version of Wish You Were Here ever going to come out?

DG: Yes. But when I last listened to it last there were still some problems, which needed sorting out before we release it.

MB: What are the chances of another David Gilmour album?

DG: I undoubtedly will make another record. I’m not ready to retire. There’s tons of stuff left over from On An Island. I just write and jot down ideas and one of these days I’ll sit down again and have a listen.

MB: … And Pink Floyd?

DG: I can see how important this Pink Floyd business gets for other people. But it just isn’t for me. I had some of the best times of my life and we created some wonderful music, but to do it again, it would be fakery. It would be trying to be something that we are not. At my age, I am entirely selfish and want to please myself. I shan’t do another Pink Floyd tour.

Feel free to comment on this interview on the NPF Forum on this thread.